In this post I want to show how Searle's philosophy of social ontology helps clarify the ritual of the LDS Sacrament. This post will be easier to understand if you read my post on Social Ontology:

Many religions believe in and perform a sacrament ritual which is often referred to as Communion. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints participates in a Sacrament meeting every week during their worship services. During the sacrament, bread and water are blessed and passed out to the congregation who eat and drink the bread and water.

Typically two young men who hold the priesthood (at the level of priests) bless the bread and water in front of the congregation. Before they bless the bread and water they break the bread into small pieces and pour water into small plastic or paper cups. At the appropriate time, one of them blesses the bread by saying the following prayer:

O God, the Eternal Father, we ask thee in the name of thy Son, Jesus Christ, to bless and sanctify this bread to the souls of all those who partake of it, that they may eat in remembrance of the body of thy Son, and witness unto thee, O God, the Eternal Father, that they are willing to take upon them the name of thy Son, and always remember him and keep his commandments which he has given them; that they may always have his Spirit to be with them. Amen. (D&C 20:77)

After they bless the bread, several other young men who hold the priesthood (at the level of deacons) pass the bread to each member of the congregation. When everyone in the congregation has eaten a piece of bread, one of the two young men then bless the water by saying the following prayer:

O God, the Eternal Father, we ask thee in the name of thy Son, Jesus Christ, to bless and sanctify this [water] to the souls of all those who drink of it, that they may do it in remembrance of the blood of thy Son, which was shed for them; that they may witness unto thee, O God, the Eternal Father, that they do always remember him, that they may have his Spirit to be with them. Amen. (D&C 20:79)

Then the water is then passed to the congregation and the sacrament ends.

What does it mean to "bless"?

To bless means to make something holy. In my last post, I wrote that "holiness" is not a physical characteristic of an object. Rather, "holiness" is a status that is assigned to an object. Therefore, when we bless the bread and water we are assigning a status to them. We are more specifically asking God to recognize a specific status, but we are not asking God to change the molecular structure or physical substance of the bread and water. Catholics on the other hand believe that the physical substance does change. (see transubstantiation)

What is the purpose of the status that is assigned to the bread and water?

The purpose of assigning a status to anything is to give that thing a function. The intended function of the bread and water is to cause the partaker to remember the Son and His atonement. The bread that we eat for breakfast does not have that function. Even if we did think of Christ every time we ate our morning toast, it would still not count as performing the function of the sacrament, because the assignment of that sacrament function must be recognized by both the partaker and by God. The bread and water are often called "emblems" because they are supposed to act as representations of Christ and His atoning sacrifice.

Why must the sacrament be recognized by both the partaker and by God?

The Sacrament ritual is a covenant that we make with God. More precisely, the sacrament is a renewal of covenants that were already made when the partaker of the sacrament was baptized. Not only do we make a promise to God, but God makes a promise with us. Therefore, the sacrament must be recognized by both parties.

What counts as covenanting with God? The act of partaking of emblems, or the act of remembering?

In order to answer this question I need to make a distinction between two types of complex actions. The first type of complex action involves doing something "by way of" doing something else. The second type of complex action involves doing something "by means of" doing something else. These types of complex actions are summarized by John Searle:

So, for example, if the chairman says, “All those in favor of the motion raise your right hand,” and I raise my right hand, I am not only raising my right hand but also voting for the motion. These are not two separate actions—raising my right hand and voting; rather, they are one action with two levels of description of the two different features of the action. Raising my right hand in that circumstance constitutes voting. I vote by way of raising my hand.

Another type of a complex action is where one intentionally does something that causes something else to occur. For example, I fire a gun by means of pulling the trigger. Here again there are not two actions—pulling the trigger and firing the gun—but only one action with two different levels of description. At the bottom level I intentionally pull the trigger. My pulling the trigger causes the gun to fire. My pulling the trigger does not cause me to fire the gun; in that context it just is firing the gun. But firing the gun is a complex act, where I intentionally achieve the effect that the gun fires by the causal “by means of” relation, whereby my bottom-level intentional movement causes the higher level effect, and the combination is the total action. (Making the Social World: The Structure of Human Civilization p36)

The act of partaking of the sacrament emblems has a "by means of" relationship with the act of remembering of Christ and His atonement. The partaking is intended to be the cause, and the remembering is the effect. Eating the bread and drinking water is also an outward sign of an inward activity.

The act of remembering has a "by way of" relationship with the act of covenanting. The remembering does not cause us to covenant with God. The remembering constitutes covenanting with God. Therefore, the intentional act of remembering is a speech act that counts as promising just as raising one's right arm counts as voting for a motion.

What do we promise to God?

The partaker of the sacrament promises to (1) always remember Christ, and (2) be willing to take upon the name of Christ, and (3) keep His commandments.

What does it mean to be willing to take upon us the name of Christ?

According to the apostle Dallin H. Oaks, the phrase "willing to take upon them the name of thy Son" has multiple meanings. In this post I will only focus on one of those meanings. To be willing to take upon the name of Christ is to be willing to accept a certain status that comes with the name. With that status comes a specific function, and with that function comes certain deontic powers such as rights and authorizations, and obligations and requirements. This pattern was illustrated to me a few days ago when my wife took the Oath of Allegiance and became a citizen of the United States of America. She essentially took upon her the name of America and became an American. She swore that she would be willing to freely take upon her certain obligations such as serving and fighting for America. Because she made this oath, she is entitled to all the rights and entitlements that come with being an American citizen.

The difference between the sacrament and the oath of Allegiance is that in the sacrament, we do not take upon ourselves the name of Christ; we only express that we are willing to do so. This implies that at some future date we will be eligible to actually take upon ourselves the name of Christ. According to Dallin H. Oaks,

Scriptural references to the name of Jesus Christ often signify the authority of Jesus Christ. In that sense, our willingness to take upon us his name signifies our willingness to take upon us the authority of Jesus Christ in the sacred ordinances of the temple, and to receive the highest blessings available through his authority when he chooses to confer them upon us. (see D&C 109:26)

This understanding thus connects the ordinance of the sacrament with the ordinances in the temple. This suggests that only those who have been to the temple can understand the deeper meaning behind sacrament because they can understand the rights and authorizations as well as obligations taken when they take upon His name in the House of the Lord.

What does God promise to us in the sacrament?

God promises to give us "His Spirit".

What is His Spirit?

It is commonly understood that His Spirit refers to the Gift of the Holy Ghost.

Why do we make promises in this ritualistic way?

A promise is a commissive speech act. As such the speaker of the promise commits herself to perform some course of action. In the case of the sacrament, the eating of the bread is a speech act. It is an act of language without the use of phonetic utterances.

The sacrament emblems could be anything because human beings can assign status functions to anything. Instead of blessing and eating bread we could bless gummy bears. Or we could have performed some bodily movement such as a dance. Or we could have simply filled out a check box on a form. But I believe that the activity of eating has symbolic significance that can more deeply and vividly help us understand the meaning behind the sacrament.

Why do we need to make promises at all?

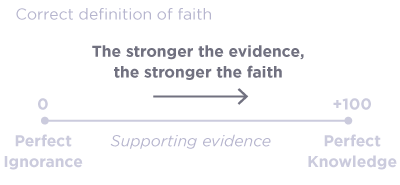

All institutional facts are extensions of language or "speech acts" that are designed to effect behavior. Institutional facts affect behavior by locking into human rationality by providing "desire-independent reasons for action." The natural desires of mankind are contrary to the will of God. These desires tend to be immoral and promote chaos. Institutional facts can promote order and morality by giving us reasons to act that are different from our natural desires. For example, when we make a promise to do something, we have engaged in a commissive speech act that gives us a reason to do that which we promised even when we do not want to follow through with our promise.

In the LDS sacrament, members covenant to continue to always remember Christ and to obey God's commandments. This gives us a reason to act independently of our natural desires. Thus, making promises gives us added motivation to follow the commandments by giving us desire-independent reasons for acting.